Read an Excerpt

From Chapter 12: Great Big Sea Over Lila G

“Free the fore and aft lines, b’ys,” Skipper Gar shouted soon after our noon-time dinner. “Raise the jib, haul away. Up the mainsail,” he ordered as we drifted away from the docks. We passed through the Narrows and tacked to the southeast.

With the warm sunny day the wind was after picking up some. A light nor’west breeze gently blew us along. I didn’t have watch until tonight so after the sails were trimmed, I could relax for most of the day. It was always exciting to be heading out on a voyage.

Not like the excitement of going to the Labrador fishery, but at least I didn’t get seasick at the start of a voyage anymore. Just a little queasy for an hour or so after leaving port. What a relief that was.

Our little vessel took the swells easily as we came about and headed south past Cape Spear. As soon as the ship left the safety of the Narrows, we were into the open North Atlantic. Even though St John’s had a wonderful protected harbour, there was no bay surrounding it. Out the Narrows, and we were at sea already.

Around midnight, we were off Cape Race, at the southeast corner of the Avalon Peninsula. We tacked around the cape and headed in a westerly direction.

The sunny day had disappeared into the fogs of the Grand Banks. This was where the warm Gulf Stream met the colder Labrador Current, not a great place for good weather. The sky darkened with heavy cloud. The wind freshened and swung around to northerly. Not a good sign. Oh well, I thought, except for a little ballast, we’re riding empty. And that won’t give us much stability. But the (Lila G) Boutler was a sturdy vessel and had faced worse.

After an evening mug-up, all hands retired for the night. Being afloat most of our working lives, we didn’t really notice the increased pitch and roll of the little schooner. It only served as a sailor’s lullaby and put us to sleep.

Sometime during the night I noticed that I wasn’t sleeping well. I woke several times. At first I put it down to a lack of fatigue. Up until now there hadn’t been much work to do. I wouldn’t be as tired as if I’d done a full day’s labour.

Next time I woke, I assumed it was due to anticipation of getting to Sydney. We were pitching and rolling pretty well; but still, not enough to worry about. I did have to brace meself in the bunk. I was after facing much worse off the Labrador plenty of times in me 20 years under canvas.

When Walt Hounsell roused me at ten minutes to four, I was already half awake.

“Up you get, Wilf, you got dog watch.”

Dog watch, from 4 to 8 a.m. was the worst one to draw. No sailor liked getting up at that ungodly hour. You felt like a dog, getting out of a warm bunk. Guess that’s why it’s called dog watch.

As I got out of the bunk and pulled on me clothes I felt the increased motion of the vessel. And I could hear the heavy wind in the rigging. It whistled through whatever crevices it could find. A cupboard door banged somewhere. The ropes and rigging whined in protest. The schooner was tossing about like a cork. As I stood, trying to get into me pants and boots, I had to hold on to the bunk and the door frame. There was no way to stand without hanging on to something.

“Better get your oilskins, Cape Ann, and mitts on s’morning, Wilf,” suggested Walt. “There’s some blow on, me son. She’s come around to a nor’easter. There’s a gale of wind out there. We already dropped most of the sails. We’re just using the jib and the double-reef foresail. Too dangerous to have any more sails aloft.”

“Why didn’t ye call me to help?”

“Cause you had next watch. Skipper wanted you to get your rest.”

“Thanks for that. I guess that’s why I didn’t sleep all that good. So much activity going on above me.”

“I checked the barometer, and the bottom’s pretty well dropped out of the glass. Hope it gets no worse.”

“At least with a nor’east wind, it’ll carry us along faster, Walt.”

“I’d just as soon we lolled along, if it’s all the same to you,” said Walt. “And I’d just as soon we didn’t have a following sea. Too dangerous.”

When a vessel experienced wind from directly behind, it allowed for maximum speed. But the downside was you had less control over your passage. All sailors would far prefer wind and waves coming towards the bow of a ship rather than the stern.

“Oh well, the Boutler is a sturdy vessel, Walt, she’s brought us through worse than this. Remember that blow we had off Turnavik a couple of year ago. I thought it was going to turn us inside out, like the whaler, Jack, did with that whale.”

The sea didn’t really scare me, but I did respect her. As long as you didn’t do anything foolish.

“Ah well, steer us true towards Cape Breton Island,” said Walt.

When I opened the forecastle hatch the wind almost took it off its hinges. I struggled to close it as quick as I could. Good thing I already had me oilskins buttoned up. Rain lashed me face and ran down me chin. The rain wasn’t coming down at all; it was blowing sideways. I stumbled aft towards the stern to take the wheel. Looking for a handhold with every step. Trying to avoid slipping on the decks awash with sea water.

There was no cabin or windsceen to protect the helmsman of a two-masted schooner. You had to stand before the wind. The only advantage with this storm was that the wind was coming from directly behind us. So the wind was actually at me back while standing at the helm. With the storm’s heavy cloud, the sky was a charcoal black. It would remain so for at least the first couple of hours of me watch.

The only navigational aid I could depend upon was the gimbal-mounted compass. Leave her on a bearing of 260 ̊, or as close as I could keep to that bearing, and everything would be fine. Walt had reminded me that we’d already passed Cape Pine lighthouse, at the mouth of Trepassey Bay, the most southerly point of Newfoundland. He hadn’t seen it though. But he had heard its foghorn, barely. We were approaching the French island of St Pierre, but well south of it. This was a shallow section of the Grand Banks. Due to the shoal waters, the seas were often much rougher here than in other locations.

“Hard night, Wilf,” shouted me old friend, Joe Atwoods, against the wind, as he handed the wheel over to me. “Hold her tight, b’y. The wind is after swinging around to east nor’east almost directly behind us. We’re running before the wind.” His voice was almost lost to the wind.

“Ah Joe, b’y, you knows what me father, Ben, says, ‘An east wind, a whistling woman, a crowing hen; brings neither good to God nor men,’” I repeated the well-known complaint about any wind from an easterly quarter.

“Call me if you needs any help,” offered Joe.

“Don’t think that will be necessary, Joe b’y. Skipper Garfield is usually up and about by six. I’ll be okay.”

“Well, hang on tight, Wilf. Better tie yourself to the wheel.”

“Have a good snooze, Joe.”

“Yeah right, you can come down and rock me to sleep.”

I held the wheel fast. I felt like I was sailing down an endless tube, with neither beginning nor end. All I could see was horizontal rain, going by me, continuously lashing me back. I understood how ships might founder on rocks and unseen sunkers. I was relieved that we were nowhere near land. Glad to be past Cape Race and Mistaken Point. Cape St Mary’s was a good ways off our starboard beam.

Time seemed to stand still. I held to the wheel in a hypnotized state. There was no clock handy, so I had no sense of time. It could have been an hour or 24 hours that passed. The little schooner alternated between going downhill over one swell, then heading up another. I felt like a pendulum on Pop Dyke’s old grandfather clock. Going up one direction and down another, never making any progress. Forever to swing in the gale.

Dawn arrived, but you’d hardly notice. The cloud cover was so dense, with the driving rain, that the black of night was barely replaced by a deep gray. This alone seemed to draw me out of a trance. I began to think that there might be an end to this gale. Storms never seemed so bad in daylight. It wouldn’t be over for awhile yet though.

Then for no particular reason I looked over me right shoulder. It just seemed like a shadow of a bird or a cloud was about to pass over me. I couldn’t believe me eyes. We were in a trough of roaring seas. Rearing over the little schooner was a gert big wave, over 30 feet high. Almost as high as the mainmast.

Before I realized what was happening the wall of water began to fall. Automatically I wove me arms into the spokes of the ship’s wheel. The water hit me in the back like a giant’s hand. I was thrown against the wheel. Thousands of tons of water struck the deck of the vessel.

A big rogue wave was after hitting the Boutler from the stern. For untold seconds I was totally surrounded by the crashing water. I couldn’t seem to catch me breath, even after the wave had abated and flowed off the decks and back into the sea. The breath was knocked right out of me.

For what seemed like minutes, I was unable to draw a breath. Jammed against the wheel I seemed paralyzed. If me arms hadn’t been wound through the wheel, I would have fallen and been swept overboard. Aware of what was going on around me, I was unable to respond. Finally, with a great gulp, I was able to draw in a rain-filled breath. A salty-tasting breath.

I was drenched. I tried to wipe some of the water away from me eyes and mouth. Looked at me hand, and saw blood. Blood dripped into me eyes. I must have struck me forehead on the wheel. I was half-groggy. Thousands of gallons of water had hit us, and then receded from the decks of the Boutler, and went back to the sea.

A minute later, Skipper Garfield appeared on deck.

“Oh me Holy Christian Oath! What happened? What happened to us, Wilf?” asked Skipper Gar. “I felt an awful big lurch from below. It threw me clear off me feet. And what a racket. Christ Almighty! What hit us? I thought we’d been rammed by another vessel.”

“Rogue wave hit us from astern, Skipper.” I was weak-kneed. “Gave me some jeezily fright, ol’ man.”

“Must have been a mighty big one, buddy. You’re lucky you weren’t washed overboard. Jesus Faithful, Wilf, your forehead is all bloody. And the rest of your face is white as Mother Rowsell’s petticoat. Here, maybe you better let me take the wheel. You go below and get that forehead looked after. And what happened to your oilskins?”

“What? What do you mean?” I was confused, and looked down at meself.

“There’s no sleeves to your jacket, ol’ man. You got no cap on, and you’re not wearing any mitts. Were you out here like that all night?”

“Oh me Lord and Savior Divine. I guess that wave must have tore ‘em right off me.”

“Well, me son, you’re a lucky man to be here, a lucky man.” repeated the skipper. “Go below and get something done to your head. Get out of them wet clothes, and get some rest. Go on, me son,” he added, like a father to a child.

I stumbled down the forecastle ladder. When I arrived at the bottom I realized that me legs were shaking. Me hands shook as I held the handrail. I felt weak for a moment. Only then did I realize the danger that I was after being exposed to. For the first time in me nautical experience, I thought maybe I’ll look for a job on land next year. This sailing racket is for men younger than me.

By the time we passed St Paul’s Island off North Cape, Cape Breton, the storm had petered out. But there was still a high swell on. I was never so relieved to reach port in Sydney. First off, we had to pass through Customs, ‘cause Canada was a foreign country in them days.

Then Skipper Gar sent me over to St Martha’s Hospital to get a couple of stitches in me forehead. I’ve carried the scar of that injury for the rest of me life. See it there, just above me left eye? It’s a reminder of what the wind and the sea can do. I see it every day when I wash me face and comb me hair.

The rest of the summer was pretty uneventful. We made four trips to Sydney for coal, and delivered it to lighthouses from Lobster Cove Head in Bonne Bay, all on down the Northern Peninsula. To places such as Point Riche, New Ferolle, Keppel Island at Port Saunders, Flower’s Island, and across the Straits to Point Amour. The granddaddy of them all, the highest lighthouse anywhere.

For some reason that we never knew at the time, the light keepers in most of them lighthouses were all Frenchmen from Quebec. We found out later on that the Newfoundland government was too cheap, and rigged up some kind of deal to get Canada to pay for some of our lighthouses. After all, they were protecting Canadian shipping in and out of the Gulf of St Lawrence.

It was a grand summer with good hard physical work. But awful dirty and dusty. And some of them lighthouses had some pretty terrible landing stages. Not even wharves. Some of the landing stages were not much more than a few planks across slippery rocks. After all, lighthouses were built in rocky, out-of-the-way places. Never in cozy coves.

The Boutler had no motor, so that maneuvering near rocks in shoal water was a test of nerve and good sailing skills. More than once, Skipper Garfield feared that we’d punch a hole in the hull on rocky shores and headlands. At the end of summer he even gave us small bonuses, for he had done really well on the coal contract.

When I arrived home in Safe Harbour at the end of September, I told Flora about me summer’s exploits. All except for that night off St Pierre.

I almost slipped up, though, when she asked about the scar on me forehead. I quickly covered meself by saying that I’d slipped and fallen on the seaweed-covered rocks at Cape Bauld lighthouse, Quirpon Island, the most northerly point in Newfoundland. She told me of her concern for me safety but I waved her off, saying it was nothing. Falls happen on slippery rocks. Which explanation she seemed to have accepted. I said no more.

Whew, I thought. I’ll never tell her about that night!

Quite an adventure, and the very next year, while looking for something else to do I found a different type of experience. Still at sea, but not so dirty as transporting coal. I went from black cargo to white salt.

Copyright © 2022 by Jerome M. Jesseau

Grand Bank fishing schooner Independence in 1921, which would have been very similar to the Lila G. Boutler.

W.R. MacAskill Nova Scotia Archives 1987-453 no. 4916

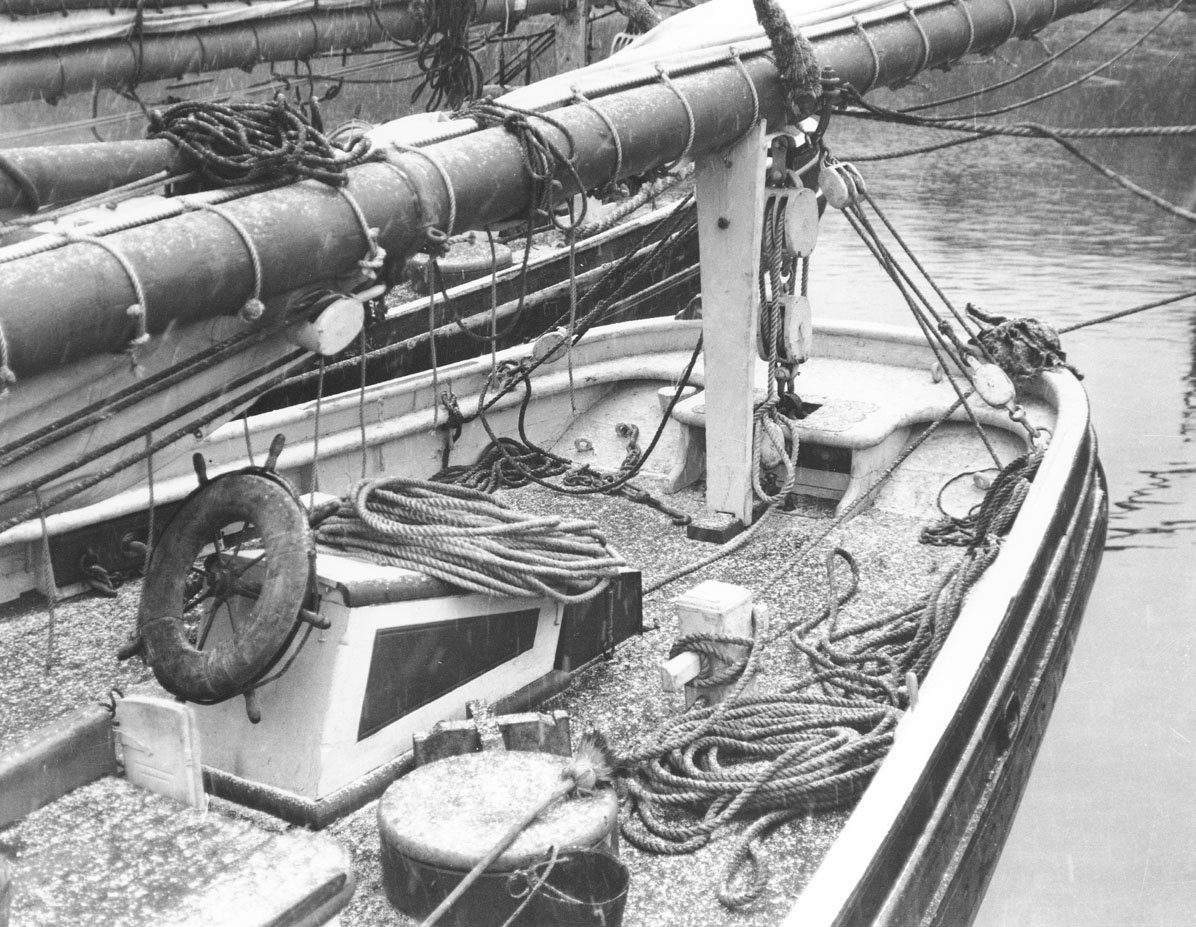

Deck detail showing helm of Grand Bank fishing schooner Bluenose anchored at Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. The exposed wheel and deck on the Lila G. Boutler would have been very similar.

W.R. MacAskill Nova Scotia Archives 1987-453 no. 109

Deck detail during storm, Grand Bank fishing schooner Bluenose. Perhaps this hints at the conditions Wilfred experienced that night off St Pierre.

W.R. MacAskill Nova Scotia Archives 1987-453 no. 226

Cover Illustration and Table of Contents

Safe Harbour, Bonavista Bay, Newfoundland. The community where Wilfred Osmond grew up. Painted by Charles Hounsell, brother-in- law of Wilfred. Used with the permission of Wallace Hounsell, who is Charles’ son, and Wilfred’s nephew. Wilfred’s home is in the lower left, near the small bridge crossing a narrow tickle.

Keep Reading Wilfred’s Story

Purchase your own copy at many local and online book retailers